American Axe by Brett McLeod | The Book Review

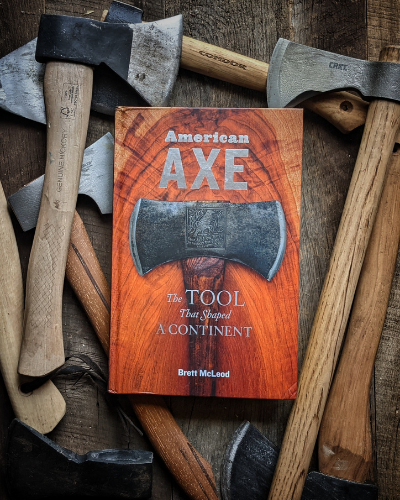

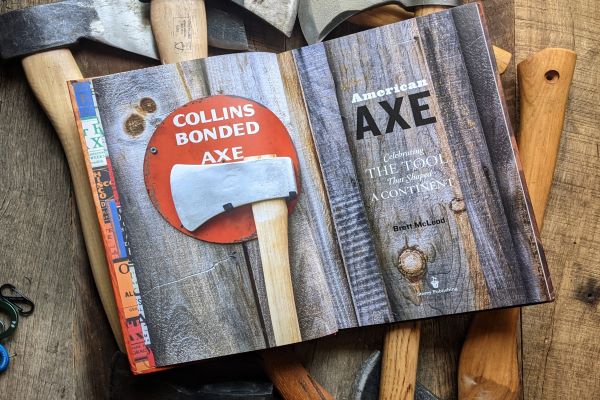

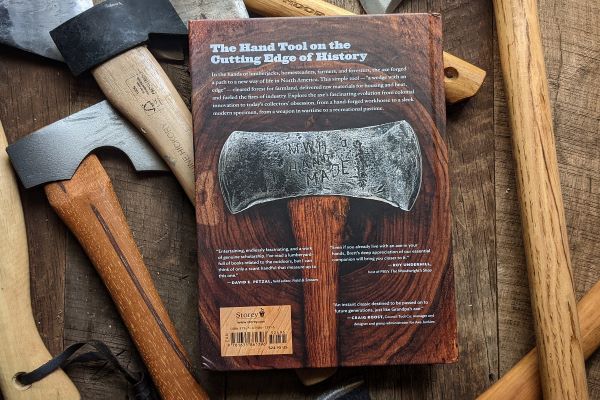

American Axe: The Tool That Shaped a Continent by Brett McLeod

When I was about 5 years old I remember watching Walt Disney’s Paul Bunyan and being completely fascinated by the giant lumberjack and his powerful axe that could fell entire forests in a few swings.

When I received a toy rubber axe a short time later, I was so energized by this mammoth lumberjack that I headed outside determined to chop down the most forested-like thing in my backyard, my father’s garden and its growing corn plants. I rested my elbow on the knob of my toy axe and inspected my work just like Paul Bunyan did in the cartoon. I could not understand that when my father observed my work he was so very angry that he spanked me and sent me to my room.

My infatuation with the axe continued throughout my early boyhood. During my time in the Boy Scouts, I was always the first volunteer to split wood. When I was 12 and wanted to have a hoop and backboard to practice shooting baskets my father and I went to a wooded area near my home and using an axe chopped down a tree and hauled it home.

My father, a craftsman if there ever was, used an axe and hatchet to create the pole for the backboard and hoop. The backboard was homemade wooden slats, and 50 years later that’s an experience that seems like yesterday.

As I got older, my interest in axes waxed and waned and at some point became part of my past. Then about a year or so ago I was in the outdoor section of a bookstore perusing books on hiking when without rhyme or reason I came across a visually impressive cover with a beguiling title.

The picture and words immediately brought back memories of my boyhood and definitely piqued my interest. I decided to purchase the book American Axe: The Tool That Shaped a Continent and I am so thankful that I did.

Woodsman and forester Brett McLeod’s book is filled with history and beautiful photographs from a time when people used axes for survival, shelter, food, and work. From its humble origins, the axe became a status symbol. The Black Raven, for example, is featured on the book’s cover and is known as a Cadillac of the axe world .

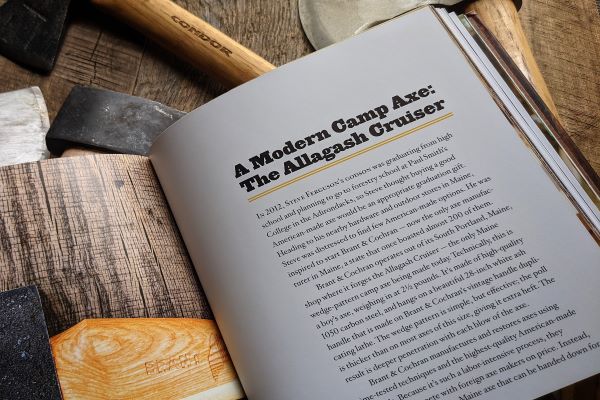

McLeod, a Paul Smith College professor, traces the history of the weapon/tool from its roots in Tuscany 5300 years ago to its recreational use today in competition. (McLeod is also the woodsmen coach at Paul Smith, a private 4-year college located on 14,000 acres in Adirondack Park, NY.) In between the beginnings and today’s recreational axe use, Mcleod examines the axe’s role in the homesteading of America, the golden age of the axe industry, modern axes, restoring that old axe in the garage, and axe throwing.

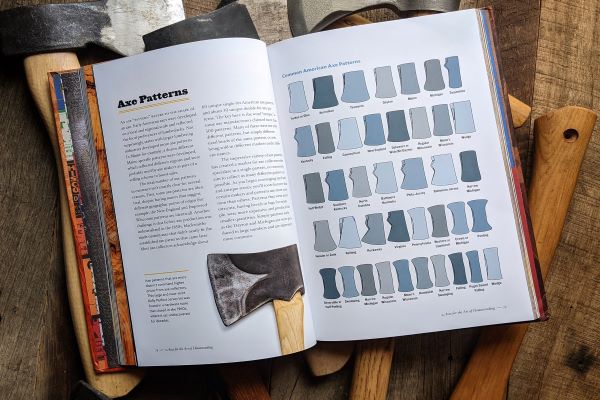

Like every good descriptive writer, Mcleod “makes the familiar new.” At first, the axe was just an axe. It was a tool that the earliest homesteaders used for “felling, bucking, peeling, notching, splitting, even chinking.” But, by about 1860, more specialized chopping tools were created to help settlers cut down trees and turn them into fuel and shelter, into heat and structures.

Soon, there were new names for the latest implements: the hatchet, boy’s axe, felling axe, maul, throwing axe, hewing axe, single hatchet, carpenter’s hatchet, mortising axe, etc. Strikingly, these tools so critical for survival, such an adjunct of the worker, have body connotations: each axe has a heel, a toe, a cheek, an eye, and a shoulder.

For more than two centuries, the axe held a leading role in settling and actually building America. From the Civil War to the mid 1960s (McLeod calls it the Golden Age of Axe making) the American axe was in high production. For example, Maine alone was home to 300 axe making companies but by the 1960s it was down to one.

It was clear that axes were moving from being a star attraction to being a minor player in the American workplace. The shift to chainsaws, migration from the country to suburbia, and the decrease in wood heat all contributed to the demise of the golden era.

Americans replaced axes with power saws and chainsaws, and the axe became banished to a corner of the garage and pulled out (if ever) only when needed to hit something.

In an attempt to stay in business, axe manufacturers reacted by merging businesses, moving to Asia and South America, and gravitating to make other tools.

For those companies that endured, it became apparent that the American consumer was no longer a lumberjack who relied on a quality tools for his survival, and instead the potential purchaser was a homeowner in a suburban setting who might utilize an axe for grubbing out an ornamental shrub or possibly splitting a few pieces of wood on a camping trip. That led to a decline in standards resulting in cut-rate, poorly made axes.

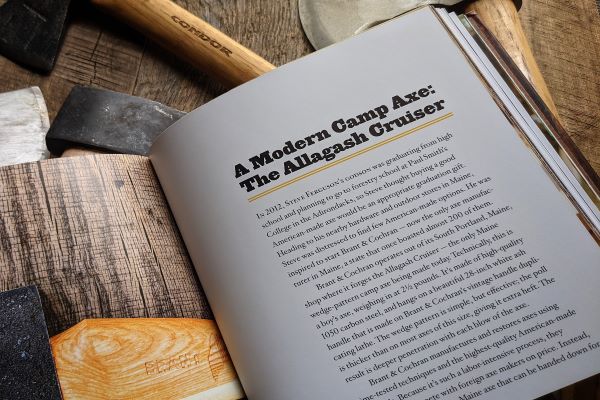

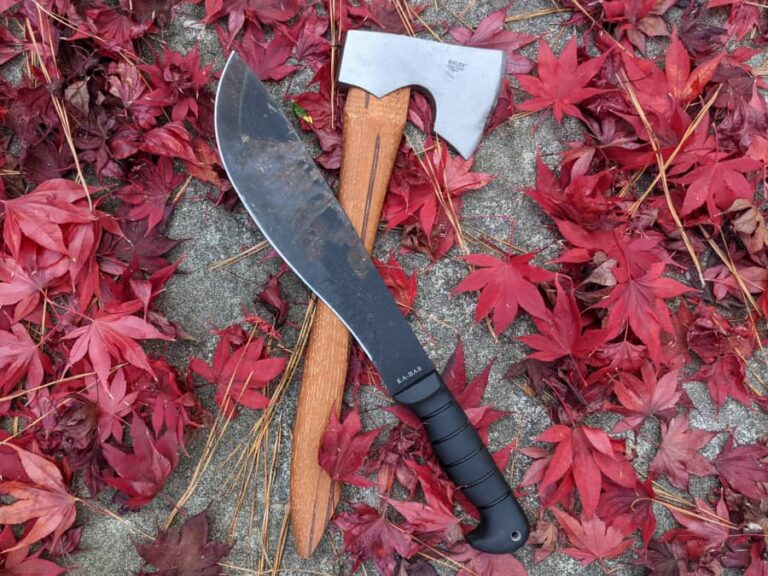

McLeod, though, writes that there is a case for optimism. There has been a recent interest by the public in traditional tools which has motivated independent blacksmiths, boutique axe makers, and a few mass producers to craft premium axes that target discriminating woodsmen. Even large scale American tool makers, such as Council Tool, are producing premium axes. We have entered a new era of quality axe making in America.

There is a wonderful chapter in the book about what really stands out is the history of the humble axe itself. I was struck by how beautiful these deceptively simple objects are. In modern life we are bombarded with technology, so it’s really easy not to take time to look at an axe, look at how they were made, look at the engravings and then see where they fit in history. You can just feel McLeod’s passion and insight in his incisive expository writing.

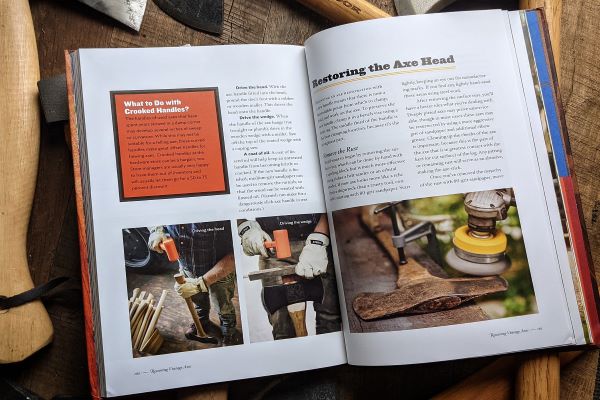

McLeod’s father had a second job as an antique dealer and as a boy he tagged along while his father was scrounging through old barns. Invariably there would be an old axe head sticking out of the dirt. He began picking them up and cleaning them and learned they were not old hunks of metal but had an interesting history behind them as well.

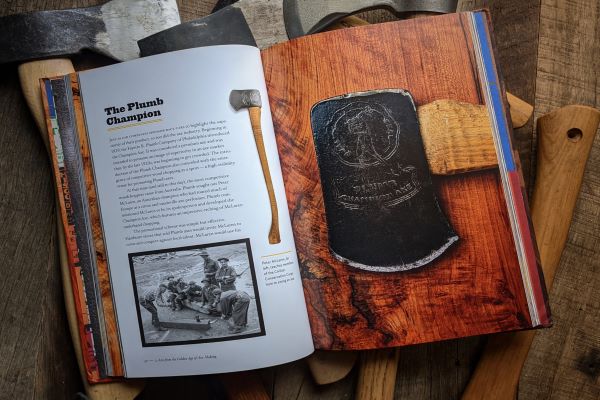

The book contains beautiful photographs of the author’s collection of axes. As a reader, these are some axes that stood out for me.

Vermont Racing Axe

A more modern, quite vicious looking axe specifically designed for competitive lumberjacking (McLeod was a competitive lumberjack). The Vermont Racing Axe might chop through a 12-inch log in something like 20 to 30 seconds.

Sager Chemical

A bow shaped axe, Sager Chemical is perfect for throwing and, because it is stamped with its year of manufacture, perfect for collecting. Much as people do vertical collections of wine where they collect every year, people will do vertical collections of Sager axes trying to get every year from 1914 and up.

Canadian Beaver

Canadian Beaver is a patterned broad axe which is giant and heavy and used for squaring a tree into lumber. You move down the log after you have scored it with a traditional felling axe and move giant dinner plate slabs from the log to smooth it out.

While reading American Axe a question arose in my mind. I recalled seeing the tool spelled ax not axe. So I decided to dig a little as to the spelling.

It seems that if Noah Webster had his way it would be spelled ax. He defined ax in his 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language and included the note “improperly written as axe.” This was at odds with Samuel Johnson’s 1755 A Dictionary of the English Language that only included axe.

Notwithstanding Noah Webster’s unyielding position, axe has carried the day as the primary spelling. Some major publications such as the Associated Press, Time, and The New York Times all favor ax over axe but the longer version prevails overall.

There were two interesting side stories in American Axe that caught my attention.

In a day when hard work was proof of character, proficiency with an axe was proof of time well served on a log. The axe culture was so pervasive and respected that when Abraham Lincoln ran for President in 1860 he became known as the rail splitter candidate, a reference to his days splitting logs into fence rails.

Although the axe was the favored tool of Honest Abe, it was also the chosen instrument of those with more iniquitous designs. Because axes and hatchets were present in virtually every home, farm, and store in America through the mid-20th century, they served as an on-hand weapon in times of frenzy and furor. While ultimately acquitted of murder, Lizzie Borden was tried for the axe murders of her father and stepmother in Fall River, Massachusetts. Four axes and a carpenter’s hatchet were found in Borden’s home but the evidence was inconclusive.

The murders and trial received widespread publicity throughout the U.S. and, along with Borden, they remain a part of American popular culture to this day. The story has been depicted in numerous films, plays, and literary works.

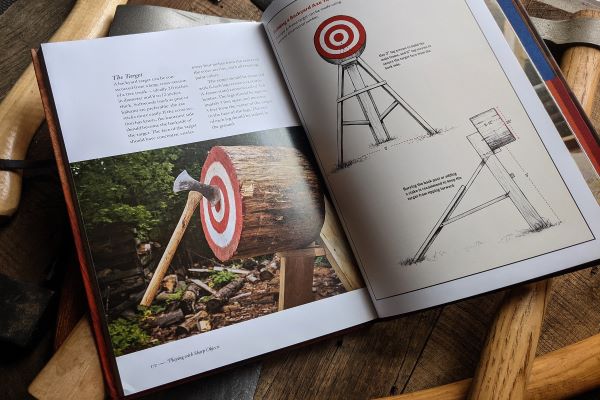

Woodsmen coach and professor McLeod writes that axes “can be a heck of a lot of fun.” So he offers advice on how to build a target, how to throw axes and tomahawks, as well as some other recreational wood chopping competitions.

When this book initially caught my eye it was the striking cover photo. However, I did wince at the extravagant sub-title, but after reading through this beautifully composed work I have been won over.

The depth and breadth is impressive. Each page offers a bit of history, a portrait of utilitarian aesthetics, and an appreciation of an implement that’s been around forever. McLeod calls the axe “a wedge with an edge.” An apt description for a tool that combines strength, utility, and design appeal.

One quibble, if this book had been written 30 years ago my interest in axes would never have waned.

Alan Dale is an experienced backpacker and adventure sports athlete who pays the bills by writing. Married with a small brood, Alan often has his kids in tow on many of his adventures. You can visit Alan here: https://siralandale.com/