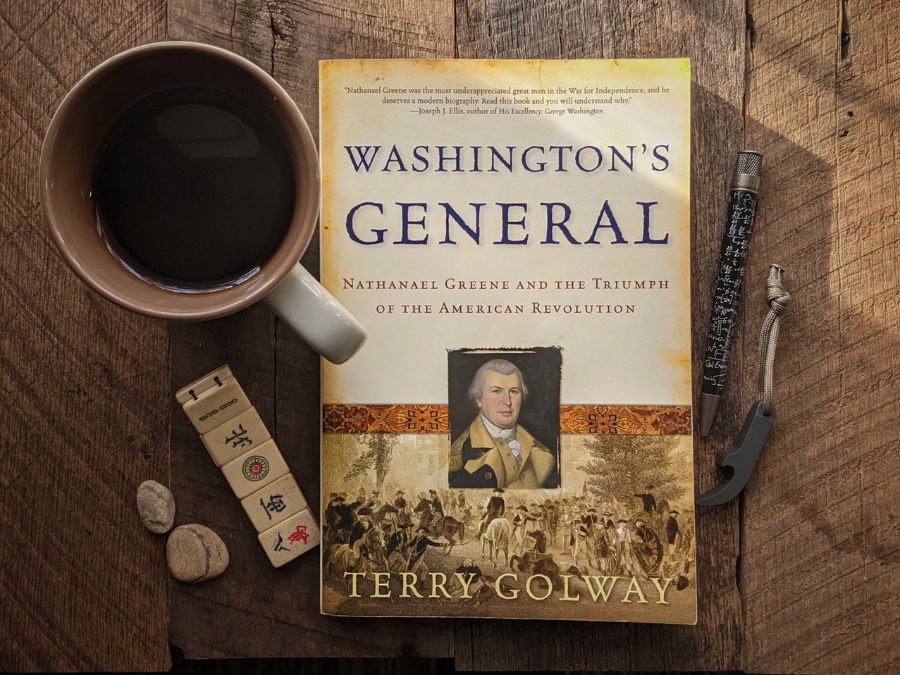

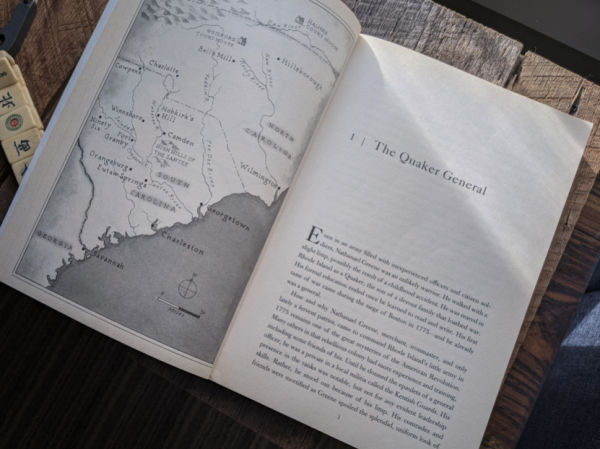

Book Review | Washington’s General: Nathanael Greene and the Triumph of the American Revolution by Terry Golway

Of all the people who achieved military fame during the American Revolution, Nathanael Greene was one of the least likely people to have earned such distinction. He was born into a well-off Quaker family, suffered from asthma, walked with a limp, was prone to self pity, and never won a battle as an independent commander. In spite of this, Greene emerged as George Washington’s most trusted general and a successful commander in his own right. So much so that Washington selected him to take over the Continental Army should he be killed or incapacitated.

As far-fetched as all this sounds, Terry Golway does an excellent job (for the most part) describing how it happened in his biography, Washington’s General. Golway tells Greene’s remarkable story (without glossing over any of Greene’s faults as a man or a soldier) and goes a long way toward resuscitating the reputation of the often-overlooked general and restoring him to his rightful place in the pantheon of Revolutionary War heroes.

No one would have foresaw Greene’s achievements as a military commander. He was born into a Rhode Island Quaker family in 1742, but as tensions between Great Britain and its North American Colonies heightened, Greene revolted against his parents’ pacifism and what was, for him, the suffocating silence of the Quaker meetings. Largely self-educated (his father did not believe in formal schooling), he read widely and had a particular affection for military histories. Within three years of his father’s death in 1770, his Quaker meeting disowned him for his immoderate military ardor and unrespectable behavior. Greene felt freed from the “obstacle” of what he considered superstitious belief.

Greene had to overcome more than his family’s religious beliefs. He walked with a limp and, although he “did not conceive it to be so great,” his fellow Rhode Island militiamen in 1774 refused to elect him as an officer as he did not appear martial enough. Greene suffered other physical ailments as well, the aforementioned asthma and problems with his right eye. Golway does not bear down on a psychological interpretation as far as he might, but he makes it apparent that war furnished the opening for Greene to break out of his “morbid self-absorption,” insecurities, and self-pitying inclinations, though these characteristics would emerge time and again with other military and political leaders.

Greene had monetary as well as psychological reasons to champion the patriot cause. The British schooner Gaspee captured a ship owned by his mercantile family in 1772. Greene’s cousin was the captain. The Greene family sued the British officer who seized the ship, and Rhode Islander’s would ultimately torch the Gaspee. Shortly thereafter, Greene lost his own business when an accidental fire reduced the family’s iron forge to ashes.

Greene’s social connections secured him a new vocation when the Rhode Island Assembly commissioned him to command the colony’s Army of Observation in 1775. A few months later, the Continental Congress made him the youngest brigadier general in the newly formed army.

Greene certainly has gaps in his biography where the narrator (and the reader) can only wonder. How did this unschooled man (though well-read) become a general in Washington’s army at 32? The mystery deepens when Golway points out that six months prior his military rank was private. Besides not promoting him for lack of a martial demeanor, his fellow Rhode Islanders pointed out that he spoiled their marching form.

In six months Greene made his leap from private to general, and there is simply no documentation, as the author points out, to explain this astonishing ascent. What seems evident to me, however, is that Greene, like Alexander Hamilton, had a gift for piquing the interest of better educated and better placed men.

Greene first met George Washington on July 4, 1775, and for the next seven years, the two frequently served together. Washington’s studied detachment intensified Greene’s insecurity. He hungered for acknowledgement from a man who did not extend lavish praise, and as a result he labored incessantly to make an impression. He drilled his troops, demanded good order in camp, and kept the paperwork moving across his desk.

Washington noticed and gave Greene command of Long Island, but he became sick and missed the battle, which was a triumph for the British. Greene then commanded New Jersey troops, but he suffered a disastrous loss when the British took Ft. Washington and 3000 prisoners. Greene heard the criticism, fretted that Washington would remove him from duty, and professed to feeling “mad, vext, sick, and sorry.”

From that low point in 1776, Greene steadily built his profession. He was with Washington at Trenton, Princeton, and Brandywine. Yet his letters to Washington show that he made demands, asking for acknowledgement of his services such as few men would dare to seek. Washington wrote “You sir, are considered my favorite officer.” As Golway points out, the passive voice concealed exactly who it was who felt that way.

Greene was with Washington at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-78 and at Morristown the following winter. So, too, were several of the generals’ wives including Caty Greene, a lively woman whom Nathanael had married in 1774 when she was 19. Caty turned heads and loved flirting with officers in camp. And Nathanael, for his part, lusted for his wife. Nearly every time she left her husband’s quarters, she returned home pregnant. Unfortunately, none of her letters to her husband survived but Golway makes clear that love was never far removed from war in Greene’s life.

At Valley Forge, Greene and Washington had their wives, and the comforts that came with their status, but common soldiers starved and froze. Greene’s foraging forays saved lives, and Washington asked him to take the position of quartermaster general, whose responsibilities included amassing and transporting supplies for troops on the march.

Greene was hesitant to accept (“Nobody ever heard of a quartermaster in history,” he complained), but he could not say no to his commander. For two years, Greene served brilliantly and restored the Continental’s supply flow. He was also not above lining his own pockets by granting contracts to companies owned by the Greene family and their partners. He kept his rank as major general and insisted on taking part in field operations. When he resigned from the post in 1780, he was seeking military glory on the battlefield only.

When the American cause finally looked lost, when Cornwallis began his sweep through the deep South on his way to Virginia, destroying two American armies during his march, Washington turned to Greene, advising him to avoid major confrontations but to keep Cornwallis moving further away from his supply depots.

In the fall of 1780, Greene was given the independent command he always craved when he was appointed to replace Horatio Gates, a man he disliked after the disastrous battle at Camden, SC. Taking over with few troops, no supplies, and few prospects of getting any, he made the most of his chance by constructing an unconventional plan based on movement and reliance on the normally undependable state militias and partisan warfare. He even proposed to the state legislatures that they enlist slaves into the army, something they turned down.

Greene’s most famous battle was the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in March, 1781, where he finally felt strong enough to meet the British head on. On the verge of winning, Lord Cornwallis snatched a costly victory from the jaws of defeat by turning his own artillery on his own men as well as Greene’s. While Cornwallis marched to his end at Yorktown, Greene moved south, taking on the enemy at Eutaw Spring, SC. Again things were going well, but the Americans got into the English rum supply and were forced to retreat when the British counterattacked. It was Greene’s last chance at achieving a battlefield victory.

Although he did not win a battle in 1781, the British paid a severe price chasing him across the South and suffering huge losses in manpower at Guilford Courthouse (Lord Cornwallis lost one-quarter of his men) and Eutaw Springs. Washington, never one to gush, told Greene simply that his accomplishments “add not a little to your reputation.”

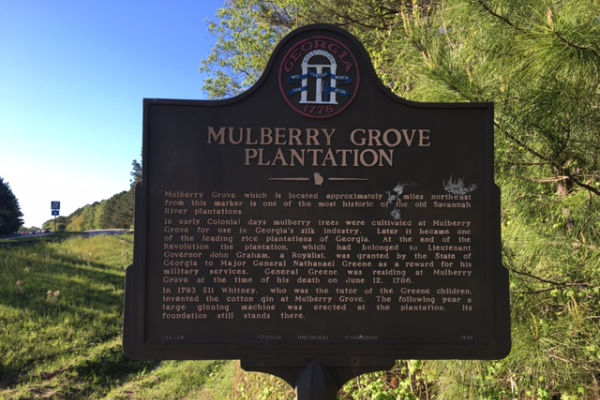

With Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown, the fighting was done. For his services in the South, Greene received gifts of landed estates from South Carolina, North Carolina, and Georgia. A 2,000 acre plantation outside of Savannah became the Greene’s home when they decided to leave Rhode Island and his failing businesses in 1785 and seek prosperity in the South, where he was revered as a hero.

The Greene’s new life included slaves but it was not profitable and Greene wrote to friends exclaiming financial distress. On June 19, 1786, while walking the grounds he suffered a sunstroke and died at age 44.

I would have hoped that Golway would have delved a little more into how someone raised as a Quaker (the first denomination opposed to slavery) could embrace owning and trading slaves. Indeed, Greene had defended the use of black troops during the war and he thought they should earn their freedom fighting for the patriot cause. I would have welcomed some discussion on this subject. If Golways’s book has a weakness, this is it.

Despite the author’s deep research from field documents, letters, diaries, and other sources, Nathanael Greene remains an ephemeral person. A man who achieved a great degree of fame but never seemed satisfied. But kudos to Terry Golway for returning a forgotten patriot to his proper place in American history.

Blair Witkowski is an avid watch nut, loves pocket knives and flashlights, and when he is not trying to be a good dad to his nine kids, you will find him running or posting pics on Instagram. Besides writing articles for Tech Writer EDC he is also the founder of Lowcountry Style & Living. In addition to writing, he is focused on improving his client’s websites for his other passion, Search Engine Optimization. His wife Jennifer and he live in coastal South Carolina.