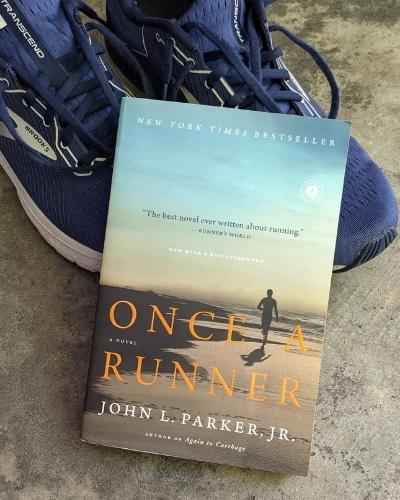

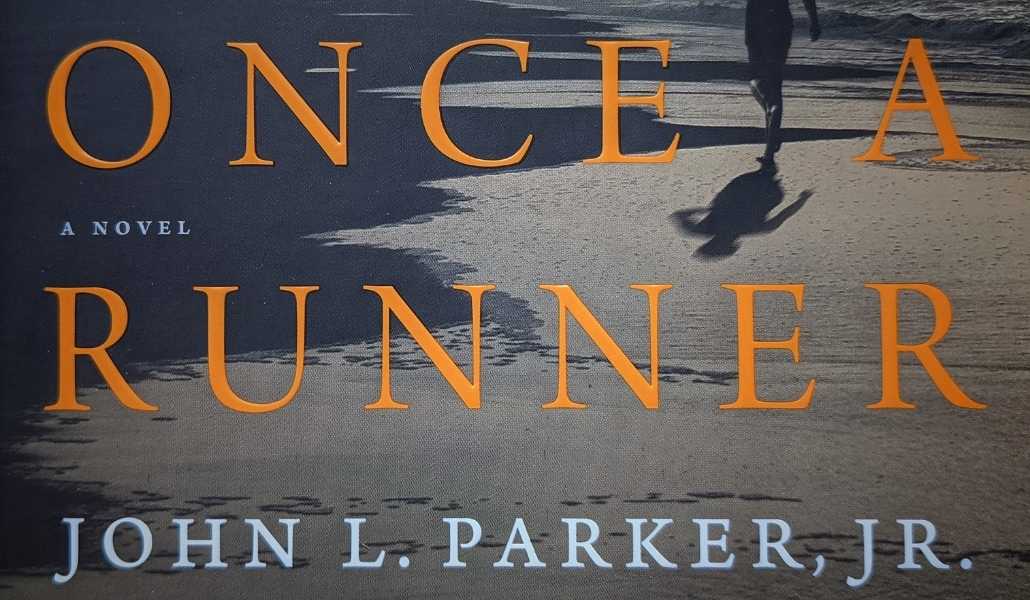

Is Once a Runner by John L. Parker Jr. A Good Book?…Not Really!

A Quick Note Before We Begin – I consider myself a runner, I have run races of all distances and terrain. I have been a runner most of my life. My friends are runners, my kids run, I have been involved in the sport for decades. I have my fair share of plastic age group trophies and hundreds of race T-Shirts. I know what On-On means and I have fought the Virgil Mountain Monster. With all these experiences in mind, I feel that I am able to add my perspective to this overrated literary work that is just a plain rambling mess. So, let’s dive in…

What does it mean that the pronounced “best novel ever written about running” (Runners World said it) is in fact at best an average novel and at worst a narrative mess?

John L. Parker, Jr., the author of Once a Runner, has said that he wrote the novel because he “felt running needed its own literature.” Parker self-published Once a Runner in 1978 with a limited run of 5,000 copies. By 2004, he had sold his last copy.

In 2007 and 2008, Bookfinder (a search engine for out of print titles) listed it as the most searched book for both years. This caught the eye of Brant Rumble, an editor at Scribner which, in 2009, republished the book. It promptly hit the New York Times bestseller list. The purported 100,000 paperback copies sold (according to Parker) and the frequently applied moniker of “cult classic” attest to the book’s appeal.

But did Parker actually further the literature of running? Once a Runner, or any novel about running (including a sequel and prequel of OAR) that has followed, has never won the critical acclaim that others have won, such as Bernard Malamud’s The Natural, Norman Maclean’s A River Run Through It, or W.C. Heinz’s The Professional (anchors of the respective cannons of baseball, fishing, and boxing).

The ironic nature of the novel’s lionization (it was the most wanted book that not enough people wanted to begin with) indicates limited appeal. There’s a reason Once a Runner has never attained a mainstream audience: it embellishes the insular world of competitive running in a way that no non-runner (not even many runners) could possibly relate to. It is written for a small section of runners and keeps casual runners and non-runners out. (This writer was a Division 1 track and cross country runner, and for many years — additional years after graduation, competed at a very high level.)

The novel is semi-autobiographical. Parker competed for the University of Florida and was a 4.06 miler. In an interview, he stated that the protagonist was an “idealized version of himself.” Once a Runner tells the story of Quenton Cassidy (a literary pretension to Faulkner’s Quentin Compson?) who will surpass his creator but will suffer and struggle to achieve his goal of running a mile in under 4 minutes. Along the way, he will lose his girlfriend and scholarship… and he almost lost me (came close to not finishing the book).

As anyone reading this likely knows, Once a Runner follows Quenton Cassidy, a collegiate miler at Southeastern University in Florida. Cassidy drops out of Southeastern University after a dress code related dispute disqualifies him from competing. He then retreats to a cabin in the woods where he puts in a huge training block (coached by Olympic gold medalist and local legend Bruce Denton) before re-emerging to run 3:52 (incognito) to defeat the world’s best miler, John Walton. Needless to say, there is more to the story, but for now this is all we need to know.

What makes a cult novel? It’s subjective and the lines blur as they often do with literature. Sometimes a cult classic is something the critics panned but the fans loved or a novel that a small section of readers gets totally besotted with. Often, cult novels remain on the fringes, offering a perspective not often seen but guaranteed to have a legion of fans claiming that the book changed their lives.

Runners fall over themselves praising Once a Runner. For years, I distanced myself from the book thinking no novel could live up to all the hype surrounding it. Finally, I gave it a go and wondered what all the fuss was about. Even runners I know very well had a passionate devotion to this story. Yet, in that praise, I detected that they were weaving their own myths around the text and thus elevating it in their own minds.

Parker created an interesting character in Quenton Cassidy but then lost his focus trying to make him bigger than he needed to be. Why?

After graduating college, Parker trained and was a member of the “mythical” Florida Track Club (FTC). Its members included 1972 Olympic marathon gold medalist Frank Shorter, legendary miler Marty Liquori, Olympians Jack Bachelor and Jeff Galloway, among other noted runners. Parker, a fine runner but not in their class, was thrilled to be training (as he mentioned in an interview) with these “giants.”

As Quenton is an idealized version of Parker (his words), I think the narrative is an idealized version of the times. Parker had a story to tell but he wanted to make it bigger. Quenton could run with the likes of a Shorter or Liquori. Quenton might be a semi-autobiographical character but in the end, he is a literary construct — a character who is more a product of imagination than memory.

There are many benefits of running but many people run and read running books because (even to a casual jogger) it confers status. You are a runner. Even jogging is considered an outward marker of achievement; it draws an American class divide between those who run and those who don’t. Serious competitive runners can take it a step further making it a holy crusade.

Parker writes about the “triumph of the human spirit” and has Quenton constantly muddying the waters with a bunch of mystical garbage. Maybe for some, that’s the attraction, but for me, it’s just another attempt to put the sport at a level that is unreachable for the normal reader but the holy grail for those “in the know.” I have never been a fan of wrapping the sport in mystery so that you exclude others. Running has always been one of the few sports that can truly be for almost everyone.

All that being said, here is why the book falls flat for me:

The Positive

In many respects, the book is an accurate picture of American distance running in the 1970s. 120-140 miles or more of running per week plus a full-time job or attending school. There was and is no secret to training (super shoes and banned substances to the contrary). Quenton Cassidy running 150 miles a week (high for a miler) is not an aberration nor is sleeping in your running shorts (easier to get out of bed for the morning run). Runners have their training idiosyncrasies and Parker knows it and nails it.

The bantering and joking during team runs is an accurate representation of college team training. Reigning in overzealous underclassmen and then increasing the pace to drop them has always been a part of team dynamics. As good as this stuff is, it can hardly be expected to carry a whole book.

The Negative

Parker seems to have bought a new thesaurus before he started his book. And just like one of Quenton’s difficult runs he gives his thesaurus a stern workout pulling out all the similes, metaphors, adjectives, and adverbs that he possibly can.

Once a Runner can be a very tedious read. The primary conflict doesn’t begin until almost two-thirds of the way into the book. Instead, the first half of the book is given over to anecdotes of the track team and its foolishness and peculiarities. At first, the stories are entertaining but by the third or fourth chapter, I found myself wondering just where this story was going. I actually had to check the book jacket to see what the blurb said about the book: a collegiate runner who gets suspended from his school team, drops out of school, and then returns to run the race of his life. Yet by halfway, he is still on the team.

Torturously, it takes a significant portion of the novel to establish the characters, and outside of Quenton none are fully realized. Parker’s excessive description of events and Cassidy’s deep thoughts left me exasperated (prepare for monotonous talk of Cassidy’s demons). Yet all these workouts, meets, races, and conversations with others about the meaning of training only masks that there is not much of a plot.

Without much of a story, the book relies on the preoccupation with the physical for its impact. Quenton’s epic workout of 60 quarters does have its moments. Yet, after that, I felt the final race was anti-climatic. Taking nine pages to build the suspense of a fairly predictable outcome was overblown, like most things in this book.

The Inexplicable

The first half of the book doesn’t seem to relate in a convincing way with the second, outside of introducing the characters. Parker spends sufficient time on six characters to make us believe they matter to the story when climatically only three do: Quenton, Bruce, and Prigman, the hard-nosed athletic director who kicks him off the team. Everybody else is just window dressing, alternately apportioning roadside philosophy, or aiding and abetting Quenton to pull off escapades in the student dorms and honor court.

Also, there is a more problematic quality to Once a Runner. Women are almost totally passed over. Denton’s wife makes only a cameo. We are made to feel Andrea is important….until she is not. This relationship is doomed to fail because in Once a Runner women are excluded from the cult. Is Andrea a token female character? Why did Parker give her a slight limp? To exclude her from the cult? Does her limp allude to the fact that she can never understand (as Quenton believes) what it takes to be an elite runner? Not sure where Parker was going with this but I’m pretty sure that I don’t want to follow.

What happened to Jerry Mizner? Best friend, training partner, but more even keel than Quenton. Takes ill, needs time to recuperate, and withdraws from the team. Quenton visits him in the hospital and then he’s written out of the book. Is this Parker’s way of saying that Mizner didn’t want it enough and it was time for Quenton to move on? Andrea’s and Jerry’s disappearances (Andrea does show up for the big race) from the narrative smack of elitism, as so do many other things in this book.

As a reader, Parker forces us to take stock of certain characters. Yet these characters become invisible. Wow, thanks, John. Nice of you to waste my time.

So what to make of Once a Runner?

Well, for one thing, it has snob appeal… but for its athletic allure, not its literary value. It gives a false narrative of what it takes to be a world-class runner. Its hyperbole misses the mark and it falls markedly short as literature. Parker chose to make world-class running a cult, and I believe this is to glorify his existence as part of that cult. To a small minority, this is the Bible. In the land of the blind, the one-eyed author is king.

I wanted to enjoy and like this book, and some readers might think I am being too harsh. However, I think the author must be held to at least a minimum standard of continuity and integration. He fails miserably.

Save yourself some time. Read Alan Sillitoe’s beautifully written, 40-page novella, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. It captures the essence of running. You will not be disappointed.

Blair Witkowski is an avid watch nut, loves pocket knives and flashlights, and when he is not trying to be a good dad to his nine kids, you will find him running or posting pics on Instagram. Besides writing articles for Tech Writer EDC he is also the founder of Lowcountry Style & Living. In addition to writing, he is focused on improving his client’s websites for his other passion, Search Engine Optimization. His wife Jennifer and he live in coastal South Carolina.