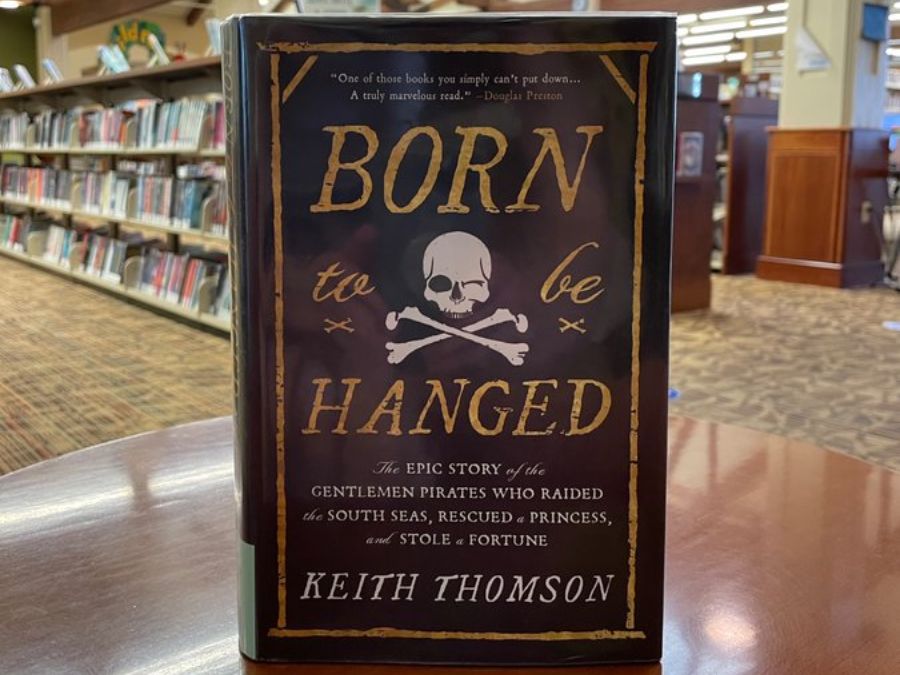

Book Review: Born to be Hanged

How much do you know about pirates?

If the word makes you think of swashbucklers who daringly capture merchant ships, bury treasure, replace limbs with hooks and pegs, capture maidens fair, and employ terms like “avast”, then you are something in the vicinity of halfway right. Like so many other aspects of history, our contemporary understanding of pirates is heavily based on Hollywood’s output, primarily the Pirates of the Caribbean films, and Hollywood is rarely under any obligation to be accurate.

Picture credit: Paulsemel.com

For those who love to read history stories that cut through the glitz and urban legends of history, Keith Thomson’s Born to be Hanged is a fantastic piece of true-to-life detail. It tells the long, non-linear journey of a company of brigands who take to the high seas of the late 1600s to seek all manner of reward. Thomson himself is not an academic, nor even a historian, but rather a former semi-pro baseball player who had been fascinated by piracy from a young age, particularly the (still undiscovered) treasure on Cocos Island off the cost of Costa Rica. His storytelling talents make Born to be Hanged a book well worth reading. Or, in some cases, well worth enduring.

The pirate life required ample bravery, promised considerable rewards, and involved more than a pinch of adventure, but those are about the nicest things you can say about the men who risked life and limb (literally) to steal a fortune. More pirates in the 1600s and 1700s perished from scurvy than from shipwreck and sword duels, a particularly miserable disease where teeth fall out and old wounds re-erupt. If you were a pirate seeking wealth, you may have survived scurvy, only then to deal with the hordes of insects that plague Central and South America, biting and laying eggs into your flesh – Thomson mentions how many pirates crossed through the jungles barefoot. Emerge unscarred from that test and you must determine which fruits are good to eat and which have a slow-acting poison that imparts days of agony before ending your time on this earth. All that, and tack on storms, bullets, drinking one’s self to death, and the eponymous risk of facing the gallows if captured.

Reading Born to be Hanged may make one wonder why any sane person would choose this career in the first place. The answer, of course, is the intrigue of piracy itself: those lucky few who did capture a treasure ship became fantastically wealthy, far more so than any humdrum profession offered back at home. The Dutch capture of an entire Spanish treasure fleet in 1628 meant the seizure of nearly twelve million gold and silver coins, enough to fund the Dutch war effort for over half a year. The company of (mostly British) pirates that Thomson writes about pursue such dreams with vigor, and at times wild abandon, certain that the next ship over the horizon will be stuffed with gold, gems, sugar, tobacco, and even lucrative parrot feathers.

The book also provides a crash course in pirate culture. The corsairs of the Spanish main were something akin to a democracy: unlike the navies of Spain or Britain or France, these sailors voted on their leaders and their next courses of action. Pirate settlements, most notably Tortuga Island off Haiti, were free of governors, bailiffs, and jails. Signing up for an expedition meant a guaranteed cut of the loot, with higher shares to those who had been in the company for longer periods. Any pirate could drop out of an expedition at any time, forfeiting their share of the loot if the risks seemed too high, although that meant they were on their own to re-reach civilization.

“A merry life and a short one” was the pirate motto, but these lives were much more often short than merry. Nor did they actually say “Argh”, but more often a simple “damn.” (Pirates did wear eyepatches when their eye was taken by an enemy blade, but also to maintain visual clarity when dropping from the bright main deck to the dark belowdecks.)

Nor were these pirates as savage as one may think. Some were highly educated, keeping diaries and records of their journey; one introduced many new words into the English language, including “guacamole.” They may have run up a flag of no quarter (i.e., no prisoners) but in the instances that they did take prisoners, their treatment was so kind and lenient that a few of the Spanish captives either volunteered helpful information or outright joined their confederacy.

Above all, Born to be Hanged reflects just how chaotic the life could be when chasing down a ship’s worth of booty. Failures and long odds often did not deter these pirates, instead leading many to double down on a wild scheme, such as capturing a fortified Spanish garrison town, in the hopes of emerging from the expedition well in the black. The journey began on the Atlantic side of Central America, led to an expedition that crossed over the Pacific, continued down the coast whenever opportunity presented itself, and resulted in nearly five full years of swashbuckling around the entire continent of South America. That the expedition returned back to Britain without a chest full of pieces of eight did not mean that it failed, for it captured the public imagination and even led to the publication of exotic books that popularized the expedition’s survivors. That many did not survive the expedition, often due to particularly gruesome ends, did not deter many more generations of ne’er-do-wells from pursuing a pirate’s life too.

Alan Dale is an experienced backpacker and adventure sports athlete who pays the bills by writing. Married with a small brood, Alan often has his kids in tow on many of his adventures. You can visit Alan here: https://siralandale.com/